BY A.D. THOMPSON

Constructor Magazine

For most of the history of the construction industry, says Cal Beyer, the topic of mental health has been taboo. Addressing things like depression and substance misuse were nonstarters.

For most of the history of the construction industry, says Cal Beyer, the topic of mental health has been taboo. Addressing things like depression and substance misuse were nonstarters.

“We see this often in male-dominated industries — in the military, heavy manufacturing, oil, gas and mining,” he explains. “People talk about ACEs (adverse childhood experiences), which looks at early childhood trauma, and construction has high rates of that — separation anxiety, single parents, people raised without a lot of stability.”

The expectation was that folks should leave their issues at home, notes Beyer, vice president for workforce risk and worker well-being for Holmes Murphy & Associates, a member of multiple Associated General Contractors (AGC) chapters.

“This industry is high risk,” he said. “Many owners require strict drug testing. People working in insurance — even me — were advocating for that because the risk was lower for contractors with testing programs.”

Alas, it’s been a strategy with consequences.

“We kicked a lot of good people to the curb,” Beyer admits. “We didn’t have great pathways for treatment and recovery.”

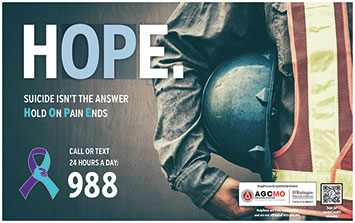

These days, however, things are trending positive. Companies across the AGC spectrum have been stepping up to address and de-stigmatize mental health among construction workers, addressing not only the industry’s high rates of suicide, but its contributing factors.

PUTTING OUT THE FIRE

Beyer describes the industry’s suicide rate as a five-alarm fire.

“It was something we needed to address before anyone could go upstream and address the things that started it,” he notes. “And the fact is that suicide was easier to talk about than mental health. And it took the pandemic before we could talk about substance misuse.”

Indeed, COVID-19 was a game changer.

“It really, really, really brought mental health issues to light,” says Pat Devero, vice president for national safety for McCarthy Holdings, Inc., who says one positive of the pandemic has been the light it shined on this, one of the industry’s darker corners. “We’d been talking, pre-COVID, about how as an organization, we could better push out our various suicide prevention campaigns.”

In the past, milestones like May’s Mental Health Awareness Month or September’s Suicide Awareness Month would trigger messaging addressing the issues, but at some point a collective light bulb went off amid McCarthy’s leadership in safety, HR and elsewhere in its national and regional divisions.

“We need to be talking about this all year long, we realized. We need to maintain a cadence of communication on this topic,” Devero said.

Once suicide was a subject out in the open, the big elephants in the room became fair game, factors like depression, anxiety and substance abuse that can put people on the road to self-harm.

Beyer said the industry had done a good job of unearthing substance misuse, “but these individuals either got no help or were left to their own devices; there wasn’t a clear path to getting people help.”

Things like union member assistance programs and allied trades assistance programs, he says, began popping up, “and 10 or so years later, some of the more established programs were expanding nationally.

“We began to see big stories about misuse, treatment and recovery,” Beyer said.

MAKING IT PERSONAL

That’s been key in the shift toward building caring cultures within firms like his, says Devero, whose career at McCarthy, a member of multiple AGC chapters, spans 17 years.

“Unfortunately, we’ve had our own experiences here with our employees, mostly in crafts. We’ve lost people to suicide. We’ve seen a number of substance abuse concerns. And once you start seeing them, start personally dealing with them, it really hits home.”

And the secret sauce in getting those resistant to messaging on a topic long taboo is making it personal.

“We have to be willing to share our own experiences if we want to break the stigma,” says Devero, who recently shared his family’s story during a company webinar. “We had a very challenging situation with our daughter, and we did the things we’ve been telling everyone else to do and — knock on wood — it worked for us.”

Telling his story made the message that much more effective.

“We have to make ourselves vulnerable, to air out some of our own laundry, if we expect employees to seek help for themselves or their family members.”

Beyer would agree wholeheartedly.

“When people let themselves be vulnerable … that’s where the magic happens,” he says. “Whoa, your employee thinks, the CEO has had these struggles, too? It takes away the fear of retaliation or reprisal.”

It’s part of what he calls the Three Vs of Leadership when it comes to addressing mental health in the workplace: visible, vocal and vulnerable.

“You have to tear down the existing culture, the macho, tough guy or gal bravado before you can build a caring one,” he says, citing inroads made by companies like McCarthy, Hensel Phelps and JE Dunn. AGC, too, has played an important role.

Director of Safety Mandi Kime of AGC Washington penned a Best Practices Guide for Mental-Health Intervention in Construction as part of her Master’s Degree thesis.

And Boldt Construction’s recently launched Gatekeeper Program is providing peer-to-peer assistance on the job, an initiative that’s in part a response to studies by the Centers for Disease Control, which determined that suicide rates in construction are four times the national average.

“A lot of guys don’t want to talk about it,” said Bob Arndt in a recent Boldt press release about the program. Arndt, a jobsite superintendent, was motivated to become a gatekeeper following the suicide of his fiancee’s father, a lifelong construction worker. “But out in the field there’s a brotherhood and hopefully they’ll open up to their peers. You’re out there as a sounding board. You’re not a professional, but you can get them help.”

Gatekeepers are peer resources, meant to help start that initial conversation.

WORKING TOGETHER

“There are so many resources available today compared even to 2016,” says Beyer, who notes that that voice of lived experience is a powerful amplified message.

“It highlights hope when a person can share that they are struggling themselves, or grief stricken by a loss, but can fight to get help for themselves or for others.”

For Devero, one among many who share so others understand the avenues through which they can seek help, it’s that simple: “You have to be willing to invest as an organization in the support you’re going to provide if you expect people to use these mechanisms.”

Top-level executives, he says, should be delivering these messages as often as safety or human resources teams or wellness professionals.

“When you have the messages coming from the top and when all the parts work together, it’s magic,” Beyer said.

“I’m seeing leadership support from associations, employers, Labor unions and health trusts. We’re starting to collaborate really well. Visibility is at an all-time high.”

Construction Safety Week has addressed mental health for two years running, with construction leadership driving topics like the whole-person concept of physical and mental well-being, or this year’s theme of United in Safety, where a field guide of resources for mental health was shared.

“It’s a huge initiative,” touts Beyer, who says he pinches himself when considering the progress made in the past decade. “And yet, there’s so much to do. Our industry is so diverse and fragmented, with lots of nooks and crannies where we need to shine light on mental health — and so it’s going to take the whole industry to bring the message.”

In the past, he notes, construction professionals were conspicuously absent in this regard, but no more.

“Now, we are leaders, breaking barriers, empowering people, sharing resources,” Beyer said. “We’re tackling this head-on — and we’re leading the way for other high-risk industries.”