ST. LOUIS LABOR RETROSPECTIVE: The Red Scare’s effect on Union membership

By ZACHARY PALITZCH

By ZACHARY PALITZCH

Archivist

Missouri State Historical Society

Following the second World War, Labor unions were a force to be reckoned with. The years 1945 and 1946 saw a massive strike wave that became the largest series of strikes in American Labor history. Dichotomous to this event, the end of WWII also ushered in the Red Scare. Everyone was afraid of a communist uprising.

Paranoid Americans came to suspect anything even vaguely leftist, which put unions under the microscope, specifically the United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers Union, which was considered as having one of the heaviest concentrations of communist leaders and members.

RECIPE FOR DISASTER

Post-war wages fell across the board. Inflation went from eight percent in 1945 to 16 percent in 1946, which was in part caused by the millions of soldiers returning home, seeking civilian jobs in the private sector. While the industrial worker’s wages increased seven percent, wages still fell behind the rising prices for consumer goods and the cost-of-living.

As a result, 25 percent of union members went on strike throughout 1946, or roughly four million workers. The most significant strikes came from the coal mining, electrical, meat packing, and steel working industries.

The explosion of strikes throughout the nation got out of hand, and while the overall strength of the Labor force was increasing, union leaders were beginning to lose control as many workers were going on strike without union sanction. The 1946 strikes marked a defining shift in the worker-leader dynamic, leading to unstable unions.

THE RED SCARE

To make matters worse, the Red Scare and McCarthyism began spreading.

The threat of communism made Americans paranoid of communist infiltration and began suspecting anything that even hinted at Communism, which meant that unions and their leaders were being watched very carefully and were often suspected of having communist ties.

The threat of being labeled a traitor by the people and government pressured Labor leaders to squash any communistic actions or members. The only way to escape suspicion was to align against Communism. As a result, Labor leaders adamantly conducted searches within unions to purge suspected and militant communist allies.

Anti-communist union leaders declared war on their leftist counterparts. This, combined with a fearful government, gave anti-communists the upper hand in their fight to rout communism within their ranks.

THE PURGE

Anti-Communist politicians gained control of Congress following the 1946 congressional elections. Instead of working with strikers and unions, Congress sought to repress the workforce by passing the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, which required unions to disclose financial and political activities. Under the act, union members also had to sign a non-communist affidavit.

Raids were growing throughout the labor force. Anti-communist factions were infiltrating leftist unions, especially unions in the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), which had the largest number of communist-led members in the late 1930s and early 1940s.

The CIO’s anti-communist leadership went on the offensive against its leftist counterparts, calling on the help of the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA) to rout communists in the CIO’s midst.

UN-AMERICAN ACTIVITIES COMMITTEE

HCUA held investigations and hearings regarding communist infiltration of Labor groups. One such union involved in HCUA’s scrutiny was the United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers Union (UE).

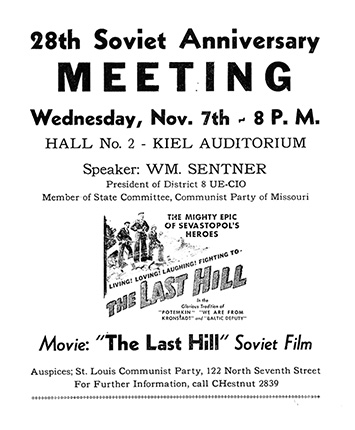

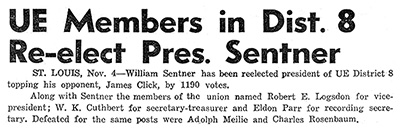

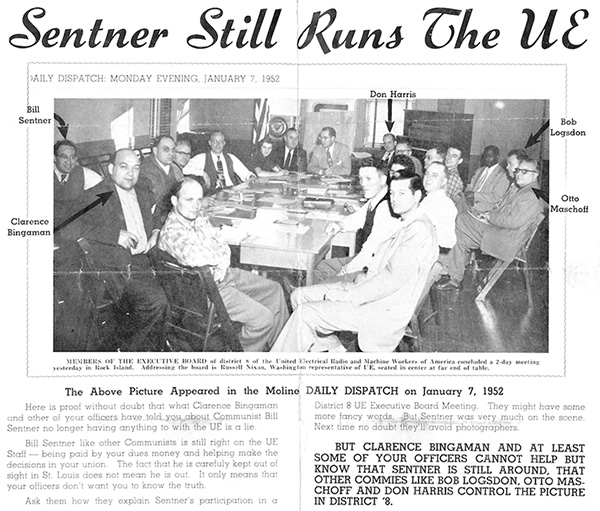

Several St. Louis UE locals were led by known communist supporters and Communist Party members. St. Louis District 8 was led by William Sentner, a known Communist Party member. While Sentner escaped HCUA’s subpoenas, one former leader of Local 1108, Henry W. Fiering, did not. Fiering was one of many officials of UE that did not sign the non-communist affidavit under the Taft-Hartley Act. He was brought before HCUA twice for being suspected as a communist, once in 1950 and again in 1952.

The hearing transcripts showed that Fiering never admitted to being affiliated with communism or the Communist Party. However, in a later interview, in 1987, Fiering stated that he began participating in communist activities in 1932. This is what originally introduced him to the Labor Movement.

In Fiering’s interview, he also mentions that the CIO hired Sentner to organize UE Local 1102, knowing that he was a member of the Communist Party. Sentner ran several successful campaigns to lead District 8, and also served as the vice president of the national UE. Sentner was able to remain in the leadership of UE throughout the purge, despite the CIO trying to install a “red-baiter,” or anti-communist, leader in District 8.

A LASTING LEGACY

The combined efforts of the CIO’s anti-communist faction and the HCUA had a drastic effect on union membership. Due to CIO’s purge, over 1.25 million members including 11 unions, were expelled, leaving it in a critically wounded state.

However, the drive to eliminate the Communist Party from unions was successful. Many St. Louis local unions developed clauses that barred Communist Party members, from joining. This allowed anti-communist members and unions to fill the gap previously held by alleged communists and far-left unions. The purges created an environment unfriendly to the Communist Party, making it very difficult for even sympathizers to operate.

Additionally, the purge had an enormous effect on union membership, which surged to about 35 percent of the workforce in the 1940s and 1950s. After the Red Scare died down in the late 1950s, membership started to decline drastically. By the mid-1960s, union membership was down to 28 percent of the workforce.

An even worse fate befell UE. At its height in the mid- to-late-1940s, UE had roughly 600,000 members. By 1960, membership dropped to 85,000.

(This ongoing series is being written by the archivists at the State Historical Society of Missouri (SHSMO) St. Louis Research Center to preserve and promote the study of Missouri’s history, including the history of the Labor Movement within the state. Contact archivists AJ Medlock, Zack Palitzsch or Erin Purdy at stlouis@shsmo.org for more information about this article or to schedule an appointment to freely view one of the many Labor collections available to the public)

Leave a Reply