Low-wage workers from fast food to academia stage massive strikes

Movement has grown to include fast-foot workers, adjunct professors, home care providers, retail employees, childcare workers, airport staff

By TIM ROWDEN

Editor

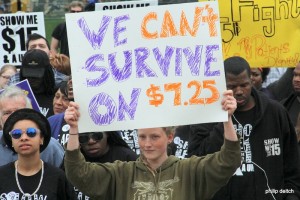

Fast-food cooks and cashiers and other low-wage workers walked off their jobs April 15 from St. Louis to Pittsburgh to Pasadena, setting off a historic wave of protests for higher pay and the freedom to join unions that stretched across industries and around the globe and inspired college students and #BlackLivesMatter activists to join in.

Workers took to the streets to show companies like Walmart and McDonalds they are willing to fight as long as it takes to win $15 and full-time, consistent hours.

Recent small wage hikes at McDonalds and Walmart just aren’t going to cut it for the many workers who struggle to put food on the table. A multi-billion dollar company like Walmart, whose owners are worth more than 42 percent of American families combined, can afford to pay its 1.3 million workers enough to support themselves and their families without having to depend on public assistance to get by.

The protests – the most widespread mobilization ever by U.S. workers seeking higher pay – occurred in 236 U.S. cities, and spanned industries from fast foot to home care to academia, stretched from Tokyo to Sao Paolo, and reached campuses like St. Louis University and Washington University.

“It’s not just our families who rely on us to make a living wage, it’s our communities as well” said Candace Young, a McDonald’s worker and a health care worker from St. Louis. “My family needs me to put food on the table, but so does the local economy. If I’m not making a living wage, I can’t support local businesses.”

St. Louis fast-food workers kicked off the protests by walking off their jobs at McDonald’s, Wendy’s Burger King, KFC, and other major national restaurant chains. Around the country, workers went on strike for the first time in Albany, NY; Asheville, NC; Greenville, MS; Montgomery, AL.; and San Jose, CA.

ST. LOUIS

St. Louis low-wage workers began the day at 6 a.m., when they put down a red carpet in the McDonald’s located at 4420 S. Broadway. Six workers proceeded to walk of their job and join the strike line. The crowd chanted “Come on out, we got your back” as Jasmine Hulsey left her position in the kitchen at McDonald’s.

“Without us to run the kitchen and the cash register, McDonald’s can’t make the billions they make every year,” Hulsey said after the chants died down. “All I’m asking for is $15 and some protection on the job.”

MORE THAN FAST FOOD

Inspired by cooks and cashiers from restaurants like McDonald’s and Burger King, adjunct professors, who are calling for $15,000 per course joined in the protests for the first time, along with home care, child care, airport, industrial laundry and Walmart workers.

Inspired by cooks and cashiers from restaurants like McDonald’s and Burger King, adjunct professors, who are calling for $15,000 per course joined in the protests for the first time, along with home care, child care, airport, industrial laundry and Walmart workers.

“The movement that fast-food cooks and cashiers started has now grown into something much bigger – made up of adjunct professors, home care providers, retail employees, childcare workers, and airport staff – all fighting for a fair shot at a decent life.” said Mary Kay Henry, International President of the Service Employees International Union, which has helped support the Fight for $15.

“Working people are going to keep speaking out in the streets, in their communities, and at the ballot box until we raise wages, strengthen the economy, and build a democracy that works for all families.”

HOME CARE WORKERS

Home care workers, who joined the Fight for $15 in a handful of cities last year, spread their protests to two-dozen cities, including St. Louis, Atlanta, New York, Los Angeles and Raleigh.

“I take care of people who don’t have families to take care of them,” LaShunda Moore, a health care worker in St. Louis. “If they didn’t have us, they wouldn’t have anyone. We need $15 and a union so we can keep doing our jobs with all the energy and love it takes.

“We have a lot of naysayers, a lot of people who don’t believe we deserve what we’re asking for,” Moore said. “But my tax dollars pay for the same things as theirs.”

Arvellea Walker, who works at Bellefontaine Gardens for $8.25 an hour, got into nursing home and rehabilitation care 10 years ago after her father died of cancer. “I got into the field to make sure other people get what they’re supposed to,” the mother of five said. “A little more money wouldn’t hurt.”

FIGHT FOR 15

GOES TO COLLEGE

On college campuses all over the country, adjunct professors, who are calling for $15,000 per course, participated in their first Fight for $15 protests since joining the movement earlier this year.

Even though many have PhD’s, adjuncts earn so little that one-in-five live below the poverty line and one-in-four are forced to rely on public assistance to scrape by.

“This is a dirty little secret in academia that nobody wants to talk about,” said Hillary Birdsong, a Spanish language adjunct at St. Louis University.

Jeffery Merritt, an adjunct professor of anthropology at Washington, Lindenwood and Maryville universities said adjunct faculty now compose a majority of teaching positions on most university campuses in the United States, and many have to take full-time jobs outside of academia just to make ends meet.

“It’s the rationalization and corporatization of higher education,” Merritt said. “Look around you St. Louis. This is what social justice looks like.”

Around 2,000 people gathered at Washington University to hear striking fast food workers, home care workers, students, and adjunct professors discuss how low wages affect them. They followed the rally with a march down Skinker and through the University City Loop, shutting down most of Delmar Blvd.

BLACK LIVES MATTER

At many of the campus protests, and in the streets throughout the day, calls for economic justice mixed with demands for racial justice as ties between the Fight for $15 and the #BlackLivesMatter continued to deepen.

A recent report from the National Employment Law Project showed that more than half of black workers in the U.S. are paid less than $15 an hour.

Workers occupied a McDonald’s on Ferguson, where rioting broke out last year following the police-involved shooting death of teenager Mike Brown, demanding living wages from billionaire corporations.

“Folks in Ferguson, and across the country, know that less poverty would mean less violence,” said Rasheen Aldridge, a leader in the Black Lives Matter movement. “These corporations have the power and the money to create good jobs that come with union protection,”

KEY ISSUE IN 2016

The urgent need for solutions to America’s low-wage crisis is already emerging as a key issue in the run-up to the 2016 election.

In The New York Times, David Leonhardt wrote, “as the 2016 presidential campaign begins to stir, the central question will be how both parties respond to the great wage slowdown.”

Leave a Reply