OPINION: Labor’s very good year – momentum matters

By Noam Scheiber

By Noam Scheiber

The New York Times

Employers do have real advantages when seeking to suppress unions. If an employer fires a worker for trying to organize a union — which is illegal — it typically takes years to litigate the case. Even if the employer is found guilty, it will at most have to pay back wages and some other “make whole” compensation, not a financial penalty for the wrongdoing. So there’s little disincentive to violating the law.

In 2021, the National Labor Relations Board found that Tesla had illegally fired a worker four years earlier for engaging in union activity, and the board ordered the company to reinstate him with back pay. Tesla appealed the decision in federal court and lost but is continuing to appeal. The worker has yet to be reinstated. Starbucks and Amazon have taken similar approaches.

Even if workers succeed at unionizing, the law offers few tools for forcing employers to negotiate a contract. Employers can wait out newly unionized workers in the hopes that they’ll become demoralized and quit, allowing the company to hire new workers who will vote the union out. In 2021, House Democrats passed a bill, the PRO Act, to address these issues. The bill died in the Senate.

That said, I’m not convinced that the organizing activity over the past few years is leading nowhere. Even as the rate of unionization fell to its lowest level on record in 2022, with only 10.1 percent of workers belonging to a union, there was still an absolute increase of nearly 300,000 unionized workers. (That is, the numerator rose substantially; it’s just that the denominator rose even more as workers re-entered the work force once the pandemic subsided.)

KEY MILESTONES

KEY MILESTONES

I think we’ve passed some key milestones.

• For example, last year Microsoft hammered out an agreement with a major union, the Communications Workers of America, that allowed employees to unionize without pushback from management and without a contentious election. Microsoft appeared to do so, at least in part, so that the union would not oppose its purchase of the video game maker Activision Blizzard.

A few hundred video game workers at Microsoft have already unionized under the agreement — a first at a major tech company — and they will likely finalize a labor contract next year. If more Microsoft workers follow suit, the attention could put pressure on other companies where workers have unionized but are struggling to negotiate a contract, like Starbucks, Microsoft’s Seattle-area neighbor.

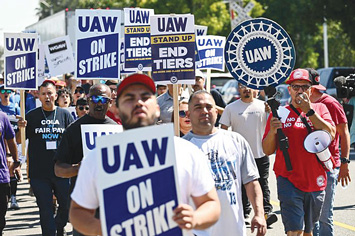

• In the auto sector, the United Automobile Workers is making a considerable investment in organizing workers at nonunion manufacturers like Tesla and Toyota. While the odds may be long at any single plant, a breakthrough at one of them could create momentum elsewhere. And the union has a more compelling case to make after negotiating large wage increases and other gains during its recent strikes at the Big Three.

• More doctors and other health care workers are also beginning to unionize amid frustrations with understaffing and overwork. Consolidation in the U.S. health care system has left many feeling like cogs within large corporations. At Walgreens and CVS, union organizers are reaching out to restive pharmacists.

ZERO TO 250

We learned from earlier periods — most notably the late 1930s, when the rate of union membership rose to nearly 27 percent from about 13 percent in just two years — that unionization is very much a social phenomenon: Workers see it succeed in one workplace, and then emulate it in their own, even if the law or employers aren’t accommodating. That tends to make it nonlinear. It can be puttering along and then suddenly accelerate. At Starbucks, the number of unionized corporate-owned stores went from zero in November of 2021 to two in December 2021 to more than 250 by the end of 2022.

One key factor in all of this will be the winner of the 2024 presidential election. On balance, Donald Trump’s appointees to the National Labor Relations Board were relatively unsympathetic to unions, while President Biden’s have been pretty helpful to them. Biden has also used his bully pulpit to back workers who are striking and seeking to unionize. There’s reason to believe that Trump would slow down the recent organizing trend while Biden would continue to enable it.

(Noam Scheiber is a Chicago-based reporter who covers workers and the workplace. Before coming to The New York Times, he spent nearly 15 years at The New Republic, where he covered economic policy and three presidential campaigns. Reprinted from The New York Times.)

Leave a Reply