Candidates’ manhood, intelligence, families were fair game

By TOM EMERY

Are you tired of relentless attack ads in which candidates rip opponents on health care, the economy, the deficit, taxes, terrorism and family values?

Are you tired of relentless attack ads in which candidates rip opponents on health care, the economy, the deficit, taxes, terrorism and family values?

Had it with political commercials that use grainy, slow-motion video with twisted expressions to make opponents look bad enough to scare small children? Sick of millions in special-interest dollars being poured into campaigns while infrastructure, schools and social programs suffer?

Fed up with hearing how the other guy is against children, seniors, teachers, schools, term limits, crime, Medicare, Medicaid, education and the environment?

BUT IT WAS WORSE

Unfortunately, it’s not a new phenomenon. It was actually worse in decades past, as elections from years ago were filthy enough to make even today’s campaign managers blush.

The media saturation of today was not the issue in the 19th Century, a time before television and the Internet. In those days, candidates and their supporters used editorials, political cartoons and pamphlets to pound their opponents into submission. Small-town newspapers were just as dirty as big-city tabloids, ripping candidates for anything and everything.

The media saturation of today was not the issue in the 19th Century, a time before television and the Internet. In those days, candidates and their supporters used editorials, political cartoons and pamphlets to pound their opponents into submission. Small-town newspapers were just as dirty as big-city tabloids, ripping candidates for anything and everything.

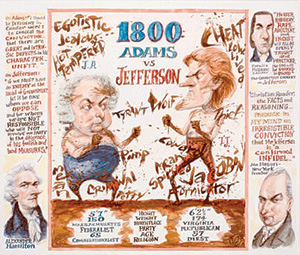

Even the earliest American Presidential campaigns were rough. In 1800, incumbent John Adams squared off against his vice-president, Thomas Jefferson, who had the second-highest number of votes in the 1796 campaign. In that era, the runner-up in the presidential election became vice-president, a practice that was abolished with the 12th Amendment in 1804.

Though the two men were former friends, few presidential races had such acrimony. Adams supporters claimed if Jefferson were elected, “murder, robbery, rape, adultery and incest will be openly taught and practiced” and voters should pick “God – and a religious president” over “Jefferson…and no God.”

In turn, one of Jefferson’s top backers published a pamphlet calling Adams “a hideous, hermaphroditical character, which has neither the force and firmness of a man, nor the gentleness or sensibility of a woman.”

Jefferson prevailed, and a petulant Adams chose not to attend the inauguration. It would be years before the men would repair their friendship.

ONLY BRIEF PAUSE

Although the nation enjoyed a brief time of political harmony dubbed the “Era of Good Feelings” in the late 1810s and early 1820s, that came to a crashing end with the bitter 1824 presidential campaign, in which John Quincy Adams edged Andrew Jackson in a controversial ending decided in the House of Representatives. Jackson supporters screamed that a backroom “corrupt bargain” was cut to get Adams in.

That rancor spilled over into the 1828 campaign, when Adams and Jackson faced off again in what may have been the dirtiest presidential campaign ever. Adams supporters focused on Jackson’s marriage, as he had famously not legally married his wife, Rachel, in 1791. That was because she had not officially divorced her first husband, a legal snafu that Jackson, an attorney, should have verified.

Though the divorce was later finalized, and they properly married in 1794, the scandal followed Jackson around, and remained a key issue in 1828. Rachel died weeks after the election, and Jackson blamed opponents for her death.

While the Adams people hammered away, “Old Hickory” responded in kind, claiming that Adams had provided women for the czar of Russia. Many historians dismiss Jackson’s charges while citing the obvious evidence that Jackson had, in fact, lived in bigamy with Rachel.

MUDSLINGING CANDIDATES

MUDSLINGING CANDIDATES

In some cases, presidential candidates have become directly involved in the mudslinging. Jackson was known to write to supportive editors, giving them tips on how to combat opposition attacks while giving them material for their own assaults.

Though he is the nation’s most beloved president today, Abraham Lincoln was reviled by opponents, who ripped him as a “baboon,” among the less offensive insults. Many anti-Lincoln political cartoons were overtly racist, blasting his stance against slavery and portraying him as a dunce or imbecile, complete with silly hats and clothing resembling a court jester.

It was common for the era, as campaigns and cartoons lambasted candidates with offensive racial depictions and sometimes portrayed them as animals or monsters. The manhood of candidates was often questioned, and cartoonists drew men in dresses to further diminish their masculinity.

FISTFIGHTS COMMON

Political rallies of the past were equally rough-and-tumble, as drunkenness and fistfights among spectators were common.

An illegitimate child was the center of the 1884 presidential campaign as Democrat Grover Cleveland, a former New York governor, had a son with a woman with a checkered past from his days back in Buffalo. Though the true parentage of the child was uncertain, Cleveland claimed responsibility, believing that he, a bachelor, had less to lose than married friends who had also been with the woman.

Republicans seized on the situation, chanting, “Ma, ma, where’s my pa? Gone to the White House, ha, ha, ha!” Cleveland voters fired back at the Republican nominee, former Secretary of State James Blaine, with their own ditty, “Blaine, Blaine, James G. Blaine! Continental liar from the state of Maine!”

Cleveland later met and married Frances Folsom in the White House in 1886, a union that captured the imagination of the nation. The campaign scandal did not hurt his popularity, as Cleveland is one of only two men to win the popular vote in three or more elections (Franklin Delano Roosevelt is the other).

(Tom Emery is a freelance writer and historical researcher from Carlinville, Ill. He may be reached at 217-710-8392 or ilcivilwar@yahoo.com.)