Garment workers battled for their place in a fleeting industry

By CARL GREEN

Correspondent

St. Louis – As great a union town as St. Louis was in the past century, attempts to organize ladies’ garment workers here became a long and hard battle that ended only when the industry departed.

The city that at first presented itself as a low-wage alternative to fast-organizing factories in New York and Chicago eventually fell victim itself to lower-wage locations both in the U.S. and overseas.

A leading labor historian, Associate Professor Rosemary Feurer of Northern Illinois University, told the story of the garment industry workers here at a recent lecture, “A Stitch in Time: St. Louis Garment and Labor History” at the Missouri Museum of History.

The appreciative crowd included many who had worked in the industry. The program was in conjunction with the museum’s “Little Black Dress” exhibit, now on through Sept. 15, and was sponsored by the Bread and Roses labor art group, but it had little to do with fashion.

The story is of an industry that was constantly on the move, wanting to maintain quality but demanding cheaper labor. St. Louis at first gained from that desire and then lost out to it. Many of its buildings remain, mainly on Washington Avenue, and memories of the struggle linger in the memories of those who worked and fought on the front lines.

The story starts in the 1890s, with city leaders promoting its working-class women and girls as silent, uncomplaining and low-wage workers, and hoping to make the city the center of the garment industry.

The story starts in the 1890s, with city leaders promoting its working-class women and girls as silent, uncomplaining and low-wage workers, and hoping to make the city the center of the garment industry.

“In the mind of the businessmen of St. Louis, the idea was that St. Louis could steal the industry from New York and Chicago,” Feurer related. “These were girls who were asked to be quiet and to produce, and they were thought of as the basis for building St. Louis – not only for making dresses.”

St. Louis’ central location and supply of warehouse space added to the campaign, and similar efforts were made for footwear and electrical products – essential industries, but not considered large, central industries such as automobile manufacturing.

COLLECTIVE ‘NO!’

Successful union organizing in the New York and Chicago garment districts appeared to St. Louis as an opportunity.

“It was an opportunity, since those areas were unionizing, to create an incentive for industry to grow here – if only we could undercut the wages of those unionized areas,” Feurer said.

“The funny thing is, these women and girls didn’t cooperate with that agenda. This began a battle in which some really amazing characters in history came forward to fight back, and to suggest a collective ‘No, that is not our vision of St. Louis!’ ”

Hannah Hennessey, a working woman of Irish descent, became the first great labor leader for the ladies’ garment workers, connecting to the national Women’s Trade Union League for help, promoting the union label, organizing clerical workers and bottlers, and pushing the United Garment Workers Union to become more aggressive.

In 1910, she led the beginning of a strike against Marx & Haas, at the time the city’s largest clothing manufacturer, for a nine-hour work day, safe conditions and union representation.

“It was just sweatshop conditions,” Feurer said. “Women were really underpaid. But what sparked that strike was that a man with tuberculosis was trying to use the elevator, and the manufacturers said, ‘Absolutely not, you’ve got to walk up the six flights of stairs.’ The women protested, he got fired, and the women walked out against those terrible conditions.”

“It was just sweatshop conditions,” Feurer said. “Women were really underpaid. But what sparked that strike was that a man with tuberculosis was trying to use the elevator, and the manufacturers said, ‘Absolutely not, you’ve got to walk up the six flights of stairs.’ The women protested, he got fired, and the women walked out against those terrible conditions.”

Unfortunately, her time in the factory also led to Hennessey contracting tuberculosis and dying once the strike was on. Her place was taken by Fannie Sellins, a UGW member who became another notable union organizer and who led a national boycott against the company. The company was supported by the Citizens Industrial Alliance group, which used private detectives to lure strikers into committing violent acts and then won court injunctions to stop them from picketing.

“This was pretty standard behavior,” Feurer explained. “Workers were encouraged not to become violent, but it was very difficult to do.”

Still, the picketing continued. Said Feurer: “Fanny’s response was ‘I’d rather go to jail than get off the streets. The streets belong to us.’

In October, 1911, the workers prevailed.

‘ST. LOUIS IDEA’

Further progress was slow. The unions tried mass walkouts during World War I, but the government stepped in and forced the workers back to work.

In St. Louis, Sellins helped create an International Ladies Garment Union (ILGU) local that organized some plants. Then she moved on to Pennsylvania, where she was murdered in 1919 on a United Mine Workers picket line.

As the unions started to take hold, the garment industry tried a new tactic – establishing plants in nearby small towns, which they intended to remain non-union and low-wage, and which could be used to compete against established plants in “whip-saw” fashion.

“It started in the shoe industry, and the idea was to get the small towns to build a garment plant or shoe plant for you, and then you could use that as your policing operation,” Feurer said. “The shoe industry actually labeled this as ‘The St. Louis Idea.’”

But the unions persisted and followed the work into the small towns, organizing the women and girls in those factories.

“They thought these young girls in farm communities and mining communities would never organize, but it was the first thing they did,” Feurer noted. “You have to say, there was a lot of spunk involved in all of this.”

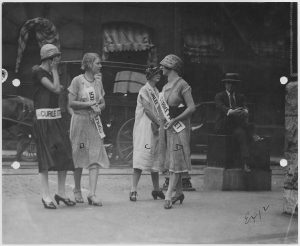

In the 1920s, the fight shifted as the vehemently anti-union Curlee Clothing became established in St. Louis as one of the nation’s largest clothing manufacturers.

The Amalgamated Clothing Workers launched a major campaign to organize the plant, supplied with national union funding to protect workers here and in New York and Chicago.

“They actually backed these workers here with a $100,000 campaign in order to make St. Louis the base of a living wage instead of a starvation wage, and they were met by a concerted class attack by Curlee, which went to extraordinary lengths.”

Curlee won a 99-year injunction against picketing at the plant – a huge victory – in 1925 after union demonstrators ripped clothing off of three women, in a tactic that backfired.

Eventually, most of the St. Louis industry was organized, but not Curlee. “They never prevailed over Curlee,” Feurer said. “Curlee not only kept that injunction alive, but when people walked out, they figured out new methods of combating them.”

HIGH POINT

The 1930s, with employment in the industry here at about 10,000, was a strong period for organizing, although companies continued to take extreme measures to block the unions, such as hiring private detectives to follow and harass organizers.

“They don’t care what it takes, they don’t care if they have to go back to not having a business, but they will not allow unionism to become dominant,” Feurer said.

After World War II, the industry begins a new tactic – leaving the area. “By the 1950s, most of the women’s garment industry is already out in Kansas, in Arkansas, in the Southwest, and it’s turning toward the South,” she said.

“There’s no time in which all of the St. Louis industry is completely organized. It is always a battle; there is always a struggle.”

In the ‘50s and ‘60s, imports started showing up, and St. Louis unionists fought hard to support the union label. In the ‘70s and ‘80s, African-Americans found jobs in the industry here. But by the 1990s, the industry was largely gone from St. Louis.

“There was never a time in which the industry simply accepted the right of people to organize,” Feurer said. “There was always this tradition in the St. Louis companies that they were cheap, they had to undercut every other part of the industry across the country, and they were the first to go south.

“There was never a time in which the industry simply accepted the right of people to organize,” Feurer said. “There was always this tradition in the St. Louis companies that they were cheap, they had to undercut every other part of the industry across the country, and they were the first to go south.

“There was always a base of unionism in the garment industry and there were some amazing things that were achieved. But the attempt to keep St. Louis in that strain of the ‘St. Louis Idea’ and to make that a reality, well, you cannot deny that either.”

TODAY’S FIGHT

The correlation today is to workers in plants overseas fighting for the same things St. Louis workers sought 100 years ago – safe working conditions, a living wage and the right to organize, as seen in street protests by workers in places such as Bangladesh and Brazil, Feurer said.

“The story of what St. Louis experienced is very similar to the story of women who are making the garments, mostly abroad, today,” she said. “They’re struggling, too, to figure out how they can build solidarity, whether they can make a label, of any kind, that can be an effective tool to keep basic, decent conditions.

“This story connects to that larger story, trying to think about how people can build an effective kind of protest and effective degree of solidarity with each other,” she added.

The industry remains one in which companies search for “greener pastures” with low wages.

“The way we perceive it is that the imports are what shut down this business, but what you have to see is this business, whether it’s shoes or the garments themselves, gradually moving its plants to cheaper labor areas,” she said. “They were already doing this long before imports were here.”

Leave a Reply